Black Families in a Gas Station Jim Crow

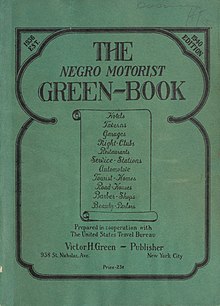

Comprehend of the 1940 edition | |

| | |

| Author | Victor Hugo Greenish |

|---|---|

| Country | United states of america |

| Language | English language |

| Genre | Guide volume |

| Publisher | Victor Hugo Green |

| Published | 1936–1966 |

The Negro Motorist Green Volume (also The Negro Motorist Green-Volume , The Negro Travelers' Light-green Volume , or simply the Green Book ) was an annual guidebook for African-American roadtrippers. Information technology was originated and published by African-American New York Urban center mailman Victor Hugo Light-green from 1936 to 1966, during the era of Jim Crow laws, when open up and often legally prescribed discrimination against African Americans especially and other not-whites was widespread. Although pervasive racial discrimination and poverty limited black car ownership, the emerging African-American middle course bought automobiles as soon as they could, just faced a variety of dangers and inconveniences along the road, from refusal of food and lodging to arbitrary arrest. In response, Greenish wrote his guide to services and places relatively friendly to African-Americans, somewhen expanding its coverage from the New York area to much of North America, too equally founding a travel agency.

Many black Americans took to driving, in office to avoid segregation on public transportation. As the writer George Schuyler put it in 1930, "all Negroes who can do so purchase an automobile equally before long every bit possible in gild to be free of discomfort, bigotry, segregation and insult".[one] Black Americans employed as athletes, entertainers, and salesmen also traveled oftentimes for work purposes using automobiles that they owned personally.

African-American travelers faced hardships such equally white-endemic businesses refusing to serve them or repair their vehicles, being refused accommodation or food by white-owned hotels, and threats of concrete violence and forcible expulsion from whites-only "sundown towns". Green founded and published the Green Book to avoid such issues, compiling resources "to give the Negro traveler information that will continue him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to make his trip more enjoyable".[2] The maker of a 2019 documentary picture about the book offered this summary: "Everyone I was interviewing talked about the customs that the Greenish Book created: a kind of parallel universe that was created past the book and this kind of hugger-mugger road map that the Greenish Book outlined".[iii]

From a New York-focused first edition published in 1936, Green expanded the work to cover much of North America, including most of the United States and parts of Canada, United mexican states, the Caribbean, and Bermuda. The Green Book became "the bible of black travel during Jim Crow",[4] enabling black travelers to detect lodgings, businesses, and gas stations that would serve them along the road. Information technology was little known exterior the African-American community. Shortly after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed the types of racial discrimination that had made the Green Volume necessary, publication ceased and information technology fell into obscurity. In that location has been a revived interest in information technology in the early 21st century in connection with studies of blackness travel during the Jim Crow era.

Four issues (1940, 1947, 1954, and 1963) have been republished in facsimile (as of Dec 2017), and have sold well.[5] Twenty-three additional issues have now been digitized by the New York Public Library Digital Collections.[6]

African-American travel experiences [edit]

Before the legislative accomplishments of the Civil Rights Movement, black travelers in the United States faced major problems unknown to near whites. White supremacists had long sought to restrict black mobility, and were uniformly hostile to black strangers.

Every bit a result, simple auto journeys for blackness people were fraught with difficulty and potential danger. They were subjected to racial profiling past police force departments ("driving while black"), sometimes seen as "uppity" or "also prosperous" merely for the human action of driving, which many whites regarded as a white prerogative. They risked harassment or worse on and off the highway.[7] A bitter commentary published in a 1947 issue of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People's magazine, The Crisis, highlighted the uphill struggle blacks faced in recreational travel:

Would a Negro like to pursue a little happiness at a theater, a beach, pool, hotel, eating house, on a train, aeroplane, or ship, a golf course, summer or wintertime resort? Would he like to stop overnight at a tourist campsite while he motors about his native land 'Seeing America First'? Well, only let him try![8]

Thousands of communities in the The states had enacted Jim Crow laws that existed after 1890;[ix] in such sundown towns, African-Americans were in danger if they stayed past sunset.[three] Such restrictions dated dorsum to colonial times, and were found throughout the The states. Subsequently the stop of legal slavery in the North and afterward in the Due south after the Civil War, almost freedmen connected to live at little more than than a subsistence level, but a minority of African-Americans gained a mensurate of prosperity. They could plan leisure travel for the first fourth dimension. Well-to-do blacks arranged large group excursions for as many as 2,000 people at a time, for instance traveling by rail from New Orleans to resorts along the declension of the Gulf of Mexico.

In the pre-Jim Crow era this necessarily meant mingling with whites in hotels, transportation and leisure facilities.[10] They were aided in this past the Ceremonious Rights Act of 1875, which had made information technology illegal to discriminate against African-Americans in public accommodations and public transportation.[eleven] They encountered a white backlash, particularly in the South, where by 1877 white Democrats controlled every state government. The Human action was alleged unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United states in 1883, resulting in states and cities passing numerous segregation laws. White governments in the South required even interstate railroads to enforce their segregation laws, despite national legislation requiring equal treatment of passengers.

The Supreme Courtroom of the United states ruled in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) that "split simply equal" accommodations were constitutional, but in practice, facilities for blacks were far from equal, more often than not being of lesser quality and underfunded. Blacks faced restrictions and exclusion throughout the United States: if non barred entirely from facilities, they could use them only at different times from whites or in (usually inferior) "colored sections".[11]

In 1917, blackness writer W. E. B. Du Bois observed that the affect of "ever-recurring race discrimination" had made it and so difficult to travel to any number of destinations, from pop resorts to major cities, that information technology was now "a puzzling query as to what to do with vacations".[11] It was a problem that came to bear upon an increasing number of black people in the first decades of the 20th century. Tens of thousands of southern African-Americans migrated from farms in the south to factories and domestic service in the north. No longer confined to living at a subsistence level, many gained dispensable income and time to engage in leisure travel.[ten]

The evolution of affordable mass-produced automobiles liberated black Americans from having to rely on the "Jim Crow cars" – smoky, battered and uncomfortable railroad carriages which were the dissever merely decidedly diff alternatives to more salubrious whites-merely carriages. One black magazine author commented in 1933, in an auto, "information technology's mighty good to be the skipper for a modify, and pilot our arts and crafts whither and where we volition. We feel like Vikings. What if our craft is blunt of olfactory organ and limited of ability and our sea is macademized; information technology's good for the spirit to merely give the old railroad Jim Crow the laugh."[x]

Centre-course blacks throughout the Us "were not at all sure how to behave or how whites would conduct toward them", equally Bart Landry puts information technology.[12] In Cincinnati, the African-American newspaper editor Wendell Dabney wrote of the state of affairs in the 1920s that "hotels, restaurants, eating and drinking places, about universally are closed to all people in whom the to the lowest degree tincture of colored claret can be detected".[11] Areas without significant black populations outside the South often refused to conform them: black travelers to Salt Lake Urban center in the 1920s were stranded without a hotel if they had to stop in that location overnight.[10] Only vi percent of the more than 100 motels that lined U.Due south. Route 66 in Albuquerque, admitted black customers.[13] Across the whole state of New Hampshire, only three motels in 1956 served African-Americans.[14]

George Schuyler reported in 1943, "Many colored families have motored all across the United States without existence able to secure overnight accommodations at a unmarried tourist camp or hotel." He suggested that black Americans would find it easier to travel abroad than in their own country.[eleven] In Chicago in 1945, St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton reported that "the city's hotel managers, by general understanding, practise not sanction the apply of hotel facilities by Negroes, peculiarly sleeping accommodations".[15] One incident reported past Drake and Cayton illustrated the discriminatory handling meted out even to blacks within racially mixed groups:

Ii colored schoolteachers and several white friends attended a luncheon at an exclusive coffee store. The Negro women were allowed to sit downward, but the waitress ignored them and served the white women. One of the colored women protested and was told that she could eat in the kitchen.[xv]

Coping with bigotry on the road [edit]

An African-American family with their new Oldsmobile in Washington, D.C., 1955

While automobiles fabricated it much easier for blackness Americans to be independently mobile, the difficulties they faced in traveling were such that, every bit Lester B. Granger of the National Urban League puts it, "so far as travel is concerned, Negroes are America'due south final pioneers".[xvi] Black travelers frequently had to comport buckets or portable toilets in the trunks of their cars because they were usually barred from bathrooms and rest areas in service stations and roadside stops. Travel essentials such equally gasoline were difficult to buy because of discrimination at gas stations.[17]

To avoid such problems on long trips, African-Americans often packed meals and carried containers of gasoline in their cars.[4] Writing of the route trips that he made as a boy in the 1950s, Courtland Milloy of the Washington Post recalled that his mother spent the evening earlier the trip frying chicken and boiling eggs then that his family would have something to eat along the way the next day.[eighteen]

Ane black motorist observed in the early on 1940s that while blackness travelers felt free in the mornings, by the early afternoon a "small deject" had appeared. By the late afternoon, "it casts a shadow of apprehension on our hearts and sours u.s. a petty. 'Where', it asks united states of america, 'will you stay this evening?'"[10] They often had to spend hours in the evening trying to find somewhere to stay, sometimes resorting to sleeping in haylofts or in their own cars if they could not find anywhere. I alternative, if information technology was available, was to adapt in advance to slumber at the homes of black friends in towns or cities along their road. However, this meant detours and an abandonment of the spontaneity that for many was a key attraction of motoring.[10]

The civil rights leader John Lewis recalled how his family prepared for a trip in 1951:

There would be no restaurant for united states to finish at until we were well out of the S, so we took our eating house right in the car with us.... Stopping for gas and to use the bathroom took careful planning. Uncle Otis had fabricated this trip before, and he knew which places along the way offered "colored" bathrooms and which were ameliorate just to pass on past. Our map was marked and our road was planned that way, past the distances between service stations where it would exist safe for us to terminate.[19]

Finding accommodation was i of the greatest challenges faced past black travelers. Not simply did many hotels, motels, and boarding houses reject to serve blackness customers, but thousands of towns across the Us alleged themselves "sundown towns", which all not-whites had to go out past sunset.[16] Huge numbers of towns beyond the country were effectively off-limits to African-Americans. By the stop of the 1960s, there were an estimated 10,000 sundown towns across the United States – including large suburbs such as Glendale, California (population 60,000 at the time); Levittown, New York (80,000); and Warren, Michigan (180,000). Over one-half the incorporated communities in Illinois were sundown towns. The unofficial slogan of Anna, Illinois, which had violently expelled its African-American population in 1909, was "Ain't No Northiggers Allowed".[xx]

Even in towns which did not exclude overnight stays by blacks, accommodations were often very limited. African-Americans migrating to California to find work in the early 1940s ofttimes plant themselves camping by the roadside overnight for lack of any hotel adaptation forth the way.[21] They were acutely aware of the discriminatory handling that they received. Courtland Milloy'southward mother, who took him and his brother on route trips when they were children, recalled:

... afterwards riding all twenty-four hours, I'd say to myself, 'Wouldn't information technology exist dainty if we could spend the dark in one of those hotels?' or, 'Wouldn't it exist keen if nosotros could stop for a existent meal and a cup of coffee?' We'd see the little white children jumping into motel swimming pools, and you all would be in the back seat of a hot car, sweating and fighting.[18]

"We cater to white trade only"; many hotels and restaurants excluded African-Americans, such as this 1 in Ohio, seen in 1938.

African-American travelers faced existent physical risks because of the widely differing rules of segregation that existed from identify to identify, and the possibility of extrajudicial violence confronting them. Activities that were accustomed in ane identify could provoke violence a few miles down the road. Transgressing formal or unwritten racial codes, even inadvertently, could put travelers in considerable danger.[22]

Even driving etiquette was affected by racism; in the Mississippi Delta region, local custom prohibited blacks from overtaking whites, to preclude their raising dust from the unpaved roads to cover white-owned cars.[10] A pattern emerged of whites purposely damaging black-endemic cars to put their owners "in their place".[23] Stopping anywhere that was not known to be safe, even to allow children in a automobile to salve themselves, presented a take chances; Milloy noted that his parents would urge him and his blood brother to control their demand to use a bathroom until they could detect a safe place to stop, as "those backroads were simply too unsafe for parents to stop to let their little black children pee".[18] Racist local laws, discriminatory social codes, segregated commercial facilities, racial profiling by police, and sundown towns fabricated road journeys a minefield of abiding dubiousness and risk.[24]

Route trip narratives by blacks reflected their unease and the dangers they faced, presenting a more complex outlook from those written by whites extolling the joys of the route. Milloy recalls the menacing environment that he encountered during his babyhood, in which he learned of "and then many black travelers ... just not making it to their destinations".[18] Even foreign black dignitaries were not immune to the discrimination that African-American travelers routinely encountered. In 1 high-profile incident, Komla Agbeli Gbedemah, the finance minister of newly independent Ghana, was refused service at a Howard Johnson'south restaurant at Dover, Delaware, while traveling to Washington, D.C., even later identifying himself past his state position to the restaurant staff.[25] The snub caused an international incident, to which an embarrassed President Dwight D. Eisenhower responded by inviting Gbedemah to breakfast at the White Firm.[26]

Repeated and sometimes violent incidents of bigotry directed against black African diplomats, particularly on U.South. Road forty between New York and Washington, D.C., led to the assistants of President John F. Kennedy setting up a Special Protocol Service Section within the Country Section to help black diplomats traveling and living within the United States.[27] The State Department considered issuing copies of The Negro Motorist Green Book to blackness diplomats, but eventually decided against steering them to blackness-friendly public accommodations as it wanted them to be treated every bit to white diplomats.[28]

John A. Williams wrote in his 1965 book, This Is My Land Also, that he did not believe "white travelers have whatever idea of how much nervus and courage it requires for a Negro to drive coast to coast in America". He achieved information technology with "nervus, courage, and a great deal of luck", supplemented past "a rifle and shotgun, a road atlas, and Travelguide, a listing of places in America where Negroes tin can stay without being embarrassed, insulted, or worse".[29] He noted that black drivers needed to be specially cautious in the Southward, where they were advised to wear a chauffeur's cap or have ane visible on the front seat and pretend they were delivering a car for a white person. Along the way, he had to endure a stream of "insults of clerks, bellboys, attendants, cops, and strangers in passing cars".[29] There was a constant need to continue his mind on the danger he faced; as he was well aware, "[black] people have a way of disappearing on the road".[29]

Role of the Light-green Book [edit]

The Dark-green Volume listed places, similar this motel in South Carolina, that provided accommodation for blackness travelers

Segregation meant that facilities for African-American motorists in some areas were express, simply entrepreneurs of varied races realized that opportunities existed in marketing goods and services specifically to blackness patrons.[x] These included directories of hotels, camps, road houses, and restaurants which would serve African-Americans. Jewish travelers, who had besides long experienced discrimination at many vacation spots, created guides for their own community, though they were at least able to visibly blend in more than easily with the general population.[30] [31] African-Americans followed adjust with publications such as Hackley and Harrison's Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers, published in 1930[32] to cover "Board, Rooms, Garage Accommodations, etc. in 300 Cities in the United states of america and Canada".[33] This book was published by Sadie Harrison, who was the Secretarial assistant of The Negro Welfare Quango (or Negro Urban League).[34]

The Negro Motorist Dark-green Volume was i of the all-time known of the African-American travel guides. It was conceived in 1932 and kickoff published in 1936 by Victor H. Light-green, a World War I veteran from New York Urban center who worked as a mail carrier and afterward as a travel agent. He said his aim was "to give the Negro traveler information that will keep him from running into difficulties, embarrassments and to brand his trip more enjoyable".[ii] According to an editorial written by Novera C. Dashiell in the 1956 edition of the Light-green Book, "the thought crystallized when not just [Green] merely several friends and acquaintances complained of the difficulties encountered; oftentimes painful embarrassments suffered which ruined a vacation or business trip".[35]

Green asked his readers to provide information "on the Negro motoring atmospheric condition, scenic wonders in your travels, places visited of interest and brusk stories on one'south motoring experience". He offered a reward of one dollar for each accepted account, which he increased to v dollars by 1941.[36] He as well obtained data from colleagues in the U.S. Postal Service, who would "ask effectually on their routes" to find suitable public accommodations.[37] The Mail service was and remains 1 of the largest employers of African-Americans, and its employees were ideally situated to inform Green of which places were safe and hospitable to African-American travelers.[38]

The Green Book's motto, displayed on the forepart embrace, urged black travelers to "Carry your Green Book with yous – You lot may need it".[35] The 1949 edition included a quote from Marker Twain: "Travel is fatal to prejudice", inverting Twain's original meaning; as Cotten Seiler puts it, "hither information technology was the visited, rather than the visitors, who would find themselves enriched by the encounter".[39] Green commented in 1940 that the Green Book had given blackness Americans "something authentic to travel by and to make traveling better for the Negro".[36]

Its principal goal was to provide accurate information on black-friendly accommodations to answer the constant question that faced black drivers: "Where will you spend the night?" As well as essential information on lodgings, service stations and garages, it provided details of leisure facilities open to African Americans, including beauty salons, restaurants, nightclubs and country clubs.[40] The listings focused on four main categories – hotels, motels, tourist homes (private residences, usually owned by African-Americans, which provided accommodation to travelers), and restaurants. They were arranged by land and subdivided by city, giving the proper noun and address of each business organisation. For an extra payment, businesses could accept their listing displayed in assuming blazon or take a star next to it to denote that they were "recommended".[xiv]

Many such establishments were run past and for African-Americans and in some cases were named later on prominent figures in African-American history. In N Carolina, such black-owned businesses included the Carver, Lincoln, and Booker T. Washington hotels, the Friendly City dazzler parlor, the Black Beauty Tea Room, the New Progressive tailor shop, the Big Buster tavern, and the Blueish Duck Inn.[41] Each edition also included feature articles on travel and destinations,[42] and included a listing of blackness resorts such equally Idlewild, Michigan; Oak Bluffs, Massachusetts; and Belmar, New Jersey.[43] The state of New Mexico was particularly recommended as a identify where well-nigh motels would welcome "guests on the footing of 'cash rather than color'".[37]

Influence [edit]

The College View Courtroom-Hotel in Waco, Texas, advertised as "Waco's Finest for Negroes" in the 1950s

The Green Book attracted sponsorship from a great number of businesses, including the African-American newspapers Call and Post of Cleveland, and the Louisville Leader of Louisville.[44] Esso (later ExxonMobil), was also a sponsor, due in function to the efforts of a pioneering African-American Esso sales representative named James "Billboard" Jackson.[36] Additionally, Esso had a black focused marketing division promote the Green Book as enabling Esso's blackness customers to "go further with less anxiety."[45] By dissimilarity, Shell gas stations were known to decline black customers.[46]

The 1949 edition included an Esso endorsement message that told readers: "As representatives of the Esso Standard Oil Co., we are pleased to recommend the Green Book for your travel convenience. Keep one on hand each year and when y'all are planning your trips, let Esso Touring Service supply y'all with maps and complete routings, and for existent 'Happy Motoring' – use Esso Products and Esso Service wherever you lot discover the Esso sign."[13] Photographs of some African-American entrepreneurs who owned Esso gas stations appeared in the pages of the Green Book.[37]

Although Greenish usually refrained from editorializing in the Dark-green Volume, he allow his readers' messages speak for the influence of his guide. William Smith of Hackensack, New Jersey, described it as a "credit to the Negro Race" in a letter published in the 1938 edition. He commented:

It is a book badly needed amid our Race since the advent of the motor historic period. Realizing the only way we knew where and how to reach our pleasure resorts was in a way of speaking, past word of mouth, until the publication of The Negro Motorist Dark-green Book ... We earnestly believe that [it] will hateful as much if not more than to us as the A.A.A. means to the white race.[44]

Earl Hutchinson Sr., the begetter of journalist Earl Ofari Hutchinson, wrote of a 1955 move from Chicago to California that "you literally didn't exit dwelling without [the Dark-green Book]".[47] Ernest Light-green, ane of the Little Rock 9, used the Green Book to navigate the 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Arkansas to Virginia in the 1950s and comments that "it was one of the survival tools of segregated life".[48] According to the civil rights leader Julian Bond, recalling his parents' apply of the Green Volume, "it was a guidebook that told you not where the all-time places were to swallow, simply where there was whatever place".[49] Bail comments:

You recollect about the things that nigh travelers take for granted, or most people today take for granted. If I go to New York City and want a hair cut, it'southward pretty piece of cake for me to find a place where that can happen, but it wasn't easy then. White barbers would non cut black peoples' hair. White dazzler parlors would not accept black women equally customers — hotels and so on, downward the line. Y'all needed the Green Book to tell you where yous tin can go without having doors slammed in your face up.[31]

While the Dark-green Book was intended to make life easier for those living under Jim Crow, its publisher looked frontward to a time when such guidebooks would no longer be necessary. Every bit Dark-green wrote, "in that location will be a solar day one-time in the near future when this guide will not take to be published. That is when we every bit a race will take equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a not bad day for united states to append this publication for then we can go equally nosotros please, and without embarrassment."[47]

Los Angeles is now considering offering special protection to the sites that kept black travelers prophylactic. Ken Bernstein, main planner for the city's Function of Historic Resource notes, "At the very to the lowest degree, these sites can exist incorporated into our city's online inventory system. They are role of the story of African Americans in Los Angeles, and the story of Los Angeles itself writ large."[50]

Publishing history [edit]

The Green Book was published locally in New York, only its popularity was such that from 1937 it was distributed nationally with input from Charles McDowell, a collaborator on Negro affairs for the U.Due south. Travel Bureau, a authorities agency.[2] With new editions published annually from 1936 to 1940, the Green Book 'due south publication was suspended during World War II and resumed in 1946.[51]

Its scope expanded greatly during its years of publication; from covering just the New York Urban center area in the get-go edition, information technology somewhen covered facilities in most of the United States and parts of Canada (primarily Montreal), Mexico, and Bermuda. Coverage was good in the eastern United States and weak in Great Plains states such equally Due north Dakota, where there were few black residents. It eventually sold around 15,000 copies per yr, distributed past mail social club, by churches and black-owned businesses every bit well equally by Esso service stations; that was unusual for the oil industry at the time but over a third of the stations were franchised to African Americans.[49] [52]

The 1937 edition, of 16 pages,[53] sold for 25 cents; by 1957, the price increased to $ane.25.[54] With the book'south growing success, Green retired from the post office and hired a small publishing staff that operated from 200 West 135th Street in Harlem. He likewise established a holiday reservation service in 1947 to take advantage of the post-war nail in automobile travel.[xiii] Past 1949, the Green Volume had expanded to more than 80 pages, including advertisements. The Green Book was printed past Gibraltar Press and Publishing Co.[55]

The 1951 Green Volume recommended that black-endemic businesses heighten their standards, equally travelers were "no longer content to pay top prices for inferior accommodations and services". The quality of black-owned lodgings was coming nether scrutiny, as many prosperous blacks found them to be second-rate compared to the white-owned lodgings from which they were excluded.[56] The 1951 "Railroad Edition" featured porters, an icon of American travel.[57] In 1952, Greenish renamed the publication The Negro Travelers' Green Book, in recognition of its coverage of international destinations requiring travel by aeroplane and send.[13]

Although segregation was still in force, past state laws in the S and oftentimes past practice elsewhere, the wide apportionment of the Light-green Volume had attracted growing interest from white businesses that wanted to tap into the potential sales of the black market place. The 1955 edition noted:

A few years afterwards its publication ... white business organization has also recognized its [The Dark-green Book 's] value and it is now in utilize by the Esso Standard Oil Co., The American Automobile Assn. and its affiliate motorcar clubs throughout the country, other automobile clubs, air lines, travel bureaus, travelers aid, libraries and thousands of subscribers.[58]

Later Greenish's death in 1960, Alma Green and her staff took over responsibility for the publication. [53]

Past the start of the 1960s, the Dark-green Volume 's market was get-go to erode. Even earlier the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, African-American civil rights activism was having the effect of lessening racial segregation in public facilities. An increasing number of middle-class African Americans were beginning to question whether guides such every bit the Light-green Book were accommodating Jim Crow by steering black travelers to segregated businesses rather than encouraging them to push for equal access. Black-owned motels in remote locations off state highways lost customers to a new generation of integrated interstate motels located almost freeway exits. The 1963 Green Volume best-selling that the activism of the civil rights movement had "widened the areas of public accommodations accessible to all", simply it defended the continued listing of black-friendly businesses considering "a family planning for a vacation hopes for one that is gratuitous of tensions and problems".[56]

The terminal edition was renamed, now called the Travelers' Dark-green Book: 1966–67 International Edition: For Holiday Without Aggravation; it was the last to be published after the Civil Rights Deed of 1964 fabricated the guide effectively obsolete past outlawing racial discrimination in public accommodation.[13] That edition included meaning changes that reflected the mail service-Civil Rights Act outlook. As the new title indicated, it was no longer merely for the Negro, nor solely for the motorist, as its publishers sought to widen its appeal. Although the content connected to proclaim its mission of highlighting leisure options for black travelers, the encompass featured a drawing of a blonde Caucasian adult female waterskiing[59]—a sign of how, as Michael Ra-Shon Hall puts it, "the Green Volume 'whitened' its surface and internationalized its scope, while still remaining true to its founding mission to ensure the security of African-American travelers both in the U.S. and abroad".[58]

Representation in other media [edit]

In the 2000s, academics, artists, curators, and writers exploring the history of African-American travel in the United states of america during the Jim Crow era revived interest in the Green Book. The result has been a number of projects, books and other works referring to the Green Book.[58] The book itself has acquired a loftier value equally a collectors' item; a "partly perished" re-create of the 1941 edition sold at auction in March 2015 for $22,500.[60] Some examples are listed below.

Digital projects [edit]

- The New York Public Library'due south Schomburg Heart for Inquiry in Black Culture has published digitized copies of 21 issues of the Dark-green Volume, dating from 1937 to 1966–1967. To accompany the digitizations, the NYPL Labs have developed an interactive visualization of the books' data to enable web users to plot their own road trips and see heat maps of listings.[61]

- The Green Book Projection, with an endorsement from the Tulsa City-Canton Library's African American Resource Center, created a digital map of the Green Book locations on historypin, invited users of the Green Book to post their photos and personal accounts about Greenish Book sites.[62]

Exhibitions [edit]

- In 2003, the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History included the Light-green Volume in an exhibition, America on the Move.

- In 2007, the book was featured in a traveling exhibition called Places of Refuge: The Dresser Trunk Project, organized by William Daryl Williams, the director of the School of Architecture and Interior Design at the University of Cincinnati. The exhibition drew on the Green Book to highlight artifacts and locations associated with travel past blacks during segregation, using dresser trunks to reflect venues such as hotels, restaurants, nightclubs and a Negro league baseball park.[58]

- In late 2014, the Gilmore Auto Museum in Hickory Corners, Michigan, installed a permanent exhibit on the Green Book that features a 1956 re-create of the book that guests can review besides every bit video interviews of those that utilized it.[63]

- In 2016, a 1941 re-create of the book was displayed at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Civilization, when the museum opened.[37]

- In June 2016, a copy of the volume on loan from The New York Public Library was featured in the Missouri History Museum's exhibition Primary Street Through St. Louis.[64]

- A re-create of the book is featured in the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum's temporary exhibition, Go far the Game: The Fight for Equality in American Sports, on view April 2018 through January xiii, 2019.[65]

Films [edit]

- Calvin Alexander Ramsey and Becky Wible Searles interviewed people who traveled with the Light-green Book as well as Victor Light-green'south relatives every bit office of the product of the documentary The Greenish Book Chronicles (2016).[66]

- 100 Miles to Lordsburg (2015) is a short flick, written by Phillip Lewis and producer Brad Littlefield, and directed by Karen Borger. It is nigh a black couple crossing New United mexican states in 1961 with assistance of the Light-green Book.[67] Set in 1961, Jack and Martha, a young, African-American couple, are driving beyond country heading to a new life in California. Jack, a Korean War Vet, and Monique, his heavily pregnant wife utilise the travel guide "The Negro Motorist Dark-green Book". Turned away from the outset motel in Las Cruces, NM they must drive 100 miles to the next town Lordsburg, NM. On the fashion, their car breaks downwards. The film achieved festival success during 2016.

- The 2018 drama flick Green Book centers a professional bout of the South taken by Don Shirley, a black musician, and his chauffeur, Tony Vallelonga, who employ the volume to discover lodgings and eateries where they can practice business concern. In so doing, Vallelonga learns nigh the various racist indignities and dangers his employer must endure, which he shares himself to a lesser extent for being Italian-American.

- The documentary film The Light-green Book: Guide to Freedom past Yoruba Richen was scheduled to first air on February 25, 2019, on the Smithsonian Channel in the United states.[68] [69] [70]

- The 2019 virtual reality documentary Traveling While Black places the viewer straight inside a portrait of African American travelers making apply of the Greenish Book.[71]

Literature [edit]

- Ramsey besides wrote a play, called The Green Book: A Play in Two Acts, which debuted in Atlanta in August 2011[54] after a staged reading at the Lincoln Theatre in Washington, DC in 2010.[4] It centers on a tourist home in Jefferson Metropolis, Missouri. A black military officeholder, his married woman, and a Jewish survivor of the Holocaust spend the dark in the home merely before the ceremonious rights activist West. East. B. Du Bois is scheduled to deliver a spoken communication in town. The Jewish traveler comes to the habitation after being shocked to find that the hotel where he planned to stay has a "No Negroes Immune" discover posted in its lobby—an allusion to the problems of discrimination that Jews and blacks both faced at the time.[49] The play was highly successful, gaining an extension of several weeks across its planned closing date.[58]

- Matt Ruff's horror-fantasy novel Lovecraft Country (2016) (set in Chicago) features a fictionalized version of Green and the Travel Guide known every bit the "Safe Negro Travel Guide". The guide is besides depicted in the HBO adaptation of the aforementioned proper noun Lovecraft Country

- In Toni Morrison's Home (2012), the narrator makes a brief reference to the Green Book: "From Green'due south travelers' volume he copies out some addresses and names of rooming houses, hotels where he would not be turned abroad" (pp. 22–23).

- A 2017 nonfiction piece of work entitled The Post-Racial Negro Green Book (Chocolate-brown Bird Books) makes use of the original Dark-green Book's format and artful equally a medium for cataloging 21st century racism toward African Americans.

- A 2019 nonfiction essay by Tiffany Marie Tucker entitled "Flick Me Rollin" considers the Green Book and her own motility in and throughout modern Chicago.

Photography projects [edit]

Architecture at sites listed in the Greenish Book is being documented past photographer Candacy Taylor in collaboration with the National Park Service'south Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program.[72] [73] She is planning to publish other materials and apps featuring such sites.[37]

See also [edit]

- Majestic Hotel, Thomasville, Georgia, historic building mentioned in the book

- AAA racial discrimination

- Harriet Beecher Stowe Business firm (known every bit Edgemont Inn, listed in 1939 edition of Green-Volume)

References [edit]

- ^ Franz, p. 242.

- ^ a b c Franz, p. 246.

- ^ a b Yeo, Debra (xix February 2019). "The real book behind Light-green Book: a means to keep blackness Americans rubber just besides a guide to having fun". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on xiv January 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ a b c Liberty du Lac, J. (September 12, 2010). "Guidebook that aided black travelers during segregation reveals vastly unlike D.C." The Washington Mail. Archived from the original on December 11, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ Flood, Alison (December 17, 2017). "Travel guides to segregated US for black Americans reissued". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved Feb x, 2018.

- ^ "The Dark-green Volume - NYPL Digital Collections". digitalcollections.nypl.org. Archived from the original on 2020-01-09. Retrieved 2017-12-29 .

- ^ Seiler, p. 88.

- ^ "Democracy Defined at Moscow". The Crisis. Apr 1947. p. 105.

- ^ "Sundown Towns – Encyclopedia of Arkansas". www.encyclopediaofarkansas.cyberspace. Archived from the original on 11 May 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f yard h Foster, Mark S. (1999). "In the Confront of "Jim Crow": Prosperous Blacks and Vacations, Travel and Outdoor Leisure, 1890–1945". The Journal of Negro History. 84 (two): 130–149. doi:x.2307/2649043. JSTOR 2649043. S2CID 149085945.

- ^ a b c d e Young Armstead, Myra B. (2005). "Revisiting Hotels and Other Lodgings: American Tourist Spaces through the Lens of Black Pleasure-Travelers, 1880–1950". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. 25: 136–159. JSTOR 40007722.

- ^ Landry, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d e Hinckley, p. 127.

- ^ a b Rugh, p. 77.

- ^ a b Drake & Cayton, p. 107.

- ^ a b Seiler, p. 87.

- ^ Sugrue, Thomas J. "Driving While Black: The Car and Race Relations in Modernistic America". Automobile in American Life and Gild. Academy of Michigan. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved August vii, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Milloy, Courtland (June 21, 1987). "Blackness Highways: Thirty Years Ago We Didn't Dare End". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February two, 2016. Retrieved January sixteen, 2016.

- ^ Wright, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Loewen, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Flamming, p. 166.

- ^ Trembanis, p. 49.

- ^ Driscoll, Jay (July 30, 2015). "An atlas of cocky-reliance: The Negro Motorist's Light-green Book (1937-1964)". National Museum of American History. Archived from the original on Dec 27, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Kelly, Kate (January 6, 2014). "The Green Volume: The First Travel Guide for African-Americans Dates to the 1930s". Huffington Postal service. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Seiler, p. 84.

- ^ DeCaro, p. 124.

- ^ Lentz & Gower, p. 149.

- ^ Wallach, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Primeau, p. 117.

- ^ Jefferson, p. 26.

- ^ a b "'Green Book' Helped African-Americans Travel Safely". NPR. September 15, 2010. Archived from the original on July seven, 2018. Retrieved August vi, 2013.

- ^ "Hackley and Harrison'south Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers". Digital Collections. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 22, 2021.

- ^ Brevard, p. 62.

- ^ "Nigh Hackley & Harrison'due south Guide for Colored Travelers". The New York Public Library. Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Goodavage, Maria (January 10, 2013). "'Greenish Book' Helped Keep African Americans Safe on the Road". PBS. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved August 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c Seiler, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d east Kahn, Eve M. (August 6, 2016). "The 'Dark-green Book' Legacy, a Buoy for Blackness Travelers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Tam, Ruth (Baronial 27, 2013). "Road guide for African American civil rights activists pointed fashion to 1963 march". The Washington Postal service. Archived from the original on June nineteen, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ Seiler, p. 92.

- ^ Seiler, p. 91.

- ^ Powell, Lew (August 27, 2010). "Traveling while black: A Jim Crow survival guide". University of North Carolina Library. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved August seven, 2013.

- ^ Rugh, p. 78.

- ^ Rugh, p. 168.

- ^ a b Seiler, p. 89.

- ^ Forest, Darren. "ExxonMobil and The Green Book". corporate.exxonmobil.com. ExxonMobil. Retrieved sixteen November 2021.

- ^ Lewis, p. 269.

- ^ a b Seiler, p. 94.

- ^ Lacey-Bordeaux, Emma; Drash, Wayne (February 25, 2011). "Travel guide helped African-Americans navigate tricky times". CNN. Archived from the original on February 28, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ a b c McGee, Celia (August 22, 2010). "The Open Road Wasn't Quite Open to All". The New York Times. Archived from the original on Apr two, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2013.

- ^ 'Green Book' sites along Route 66 kept traveling African Americans safe. L.A. is at present considering giving those spots special protection Archived 2016-06-02 at the Wayback Automobile. Los Angeles Times, May 17, 2016.

- ^ Landry, p. 57.

- ^ "A look inside the Green Book, which guided Black travelers through a segregated and hostile America". Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved Baronial xx, 2021.

- ^ a b "A look within the Green Book, which guided Black travelers through a segregated and hostile America". Archived from the original on August 23, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ a b Towne, Douglas (July 2011). "African-American Travel Guide". Phoenix Magazine. p. 46.

- ^ "Total text of "The Negro Motorist Green Book, 1949"". Internet Archive. October 23, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ a b Rugh, p. 84.

- ^ Taylor, Candacy (2020). Overground Railroad: The Green Book Roots of Black Travel in America. pp. 178–nine.

- ^ a b c d e Hall, Michael Ra-Shon (2014). "The Negro Traveller's Guide to a Jim Crow South: Negotiating racialized landscapes during a dark period in U.s. cultural history, 1936–1967". Postcolonial Studies. 17 (iii): 307–14. doi:10.1080/13688790.2014.987898. S2CID 161738985.

- ^ "Travelers' Green Volume: 1966–67 International Edition". NYPL Digital Collections. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ "Auction 2377 Lot 516". Swann Sale Galleries. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved Dec 26, 2015.

- ^ "The Green Volume". NYPL digitalcollections.nypl.org. Archived from the original on 9 Jan 2020. Retrieved 17 Apr 2019.

- ^ "Green Volume Projection" Archived 2018-03-12 at the Wayback Motorcar. historypin.org. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ "Gilmore Auto Museum – Special Exhibits". Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2015.

- ^ Wanko, Andrew (September 22, 2016). "Navigating Race: Route 66 and the Dark-green Volume" Archived 2020-06-15 at the Wayback Machine. Road 66: Principal Street Through St. Louis. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- ^ (Untitled) Archived 2021-03-08 at the Wayback Machine. Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum/Twitter. June 21, 2018. Retrieved Dec 3, 2019.

- ^ Wible Searles, Becky; Ramsey, Calvin Alexander (2015). "The Green Book Chronicles". Archived from the original on 2016-01-09. Retrieved 2016-01-18 .

- ^ Kahn, Eve M. (August vi, 2015). "The 'Dark-green Book' Legacy, a Beacon for Black Travelers". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August ten, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- ^ Yeo, Debra (19 Feb 2019). "The existent book behind Light-green Volume: a means to keep blackness Americans safe merely as well a guide to having fun – The Star". The Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 14 January 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ^ 'Guide To Liberty' Documentary Chronicles The Real Life 'Green Book' Archived 2019-02-26 at the Wayback Automobile. Interview with filmmaker Yoruba Richen on Fresh Air – NPR February 25, 2019. Retrieved Feb 25, 2019

- ^ Giorgis, Hanmah (February 23, 2019). "The Documentary Highlighting the Existent Green Volume". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on Feb 26, 2019. Retrieved Feb 26, 2019.

- ^ Dream McClinton, "Traveling While Black: behind the center-opening VR documentary on racism in America" Archived 2020-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian, September iii, 2019.

- ^ Candacy Taylor, "Sites of Sanctuary: The Negro Motorist Green Book" Archived 2018-08-28 at the Wayback Car, Taylor Fabricated Culture.

- ^ "Route 66 and the Historic Negro Motorist Green Book" Archived 2017-01-04 at the Wayback Machine. National Park Service.

Bibliography [edit]

- Brevard, Lisa Pertillar (2001). A Biography of Eastward. Azalia Smith Hackley, 1867–1922, African-American Singer and Social Activist. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN9780773475755.

- DeCaro, Louis A. (1997). On the Side of My People: A Religious Life of Malcolm X. NYU Press. ISBN9780814718919.

- Drake, St. Clair; Cayton, Horace A. (1970). Black City: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City. Academy of Chicago Press. ISBN9780226162348.

- Flamming, Douglas (2009). African Americans in the West . ABC-CLIO. ISBN9781598840032.

- Franz, Kathleen (2011). "African-Americans Take to the Open Road". In Franz, Kathleen; Smulyan, Susan (eds.). Major Problems in American Popular Civilization. Cengage Learning. ISBN9781133417170.

- Griffin, John Howard (2011). Black Similar Me : the definitive Griffin manor edition, corrected from original manuscripts. Outset pub. 1961. Wings Press. ISBN9780916727680.

- Hinckley, Jim (2012). The Route 66 Encyclopedia. Voyageur Printing. ISBN9780760340417.

- Jefferson, Alice Rose (2007). Lake Elsinore: A Southern California African American Resort Area During the Jim Crow Era, 1920s–1960s, and the Challenges of Historic Preservation Commemoration. ISBN9780549391562.

- Landry, Bart (1988). The New Black Middle Grade. University of California Printing. ISBN9780520908987.

- Lentz, Richard; Gower, Karla One thousand. (2011). The Opinions of Mankind: Racial Problems, Printing, and Progaganda in the Cold War. University of Missouri Press. ISBN9780826272348.

- Lewis, Tom (2013). Divided Highways: Edifice the Interstate Highways, Transforming American Life. Cornell University Press. ISBN9780801467820.

- Loewen, James W. (2006). "Sundown Towns". In Hartman, Chester W. (ed.). Poverty & Race in America: The Emerging Agendas. Lexington Books. ISBN9780739114193.

- Primeau, Ronald (1996). Romance of the Road: The Literature of the American Highway. Bowling Green Country University Popular Press. ISBN9780879726980.

- Rugh, Susan Sessions (2010). Are We There Yet?: The Aureate Historic period of the American Family Vacation. University of Kansas Publications. ISBN9780700617593.

- Seiler, Cotten (2012). "'So That We as a Race Might Have Something Accurate to Travel By': African-American Automobility and Cold-War Liberalism". In Slethaug, Gordon E.; Ford, Stacilee (eds.). Hit the Road, Jack: Essays on the Culture of the American Road. McGill-Queen'southward Press. ISBN9780773540767.

- Taylor, Candacy (3 November 2016). "The Roots of Route 66". The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- Trembanis, Sarah L. (2014). The Set-Up Men: Race, Culture and Resistance in Black Baseball. McFarland. ISBN9780786477968.

- Wallach, Jennifer Jensen (2015). Dethroning the Mendacious Pork Chop: Rethinking African American Foodways from Slavery to Obama. Academy of Arkansas Press. ISBN9781557286796.

- Wright, Gavin (2013). Sharing the Prize. Harvard University Press. ISBN9780674076440.

Further reading [edit]

- Flood, Alison (December 19, 2017). "Travel guides to segregated The states for blackness Americans reissued". The Guardian . Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- Melt, Lisa D., Maggie Eastward.C. Jones, David Rosé, Trevon D. Logan. 2020. "The Green Books and the Geography of Segregation in Public Accommodations". NBER paper.

- Monahan, Meagan Thousand. (January 3, 2013). "'The Green Book': A Representation of the Black Middle Class and Its Resistance to Jim Crow through Entrepreneurship and Respectability". Williamsburg, VA: The College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on April x, 2015.

- Monahan, Meagan Grand. (Fall 2016). "The Green Volume: Safely Navigating Jim Crow America". The Dark-green Handbag.

- Pilkington, Ed. "From the Green Book to Facebook: How Black People Still Need to Outwit Racists in Rural America", The Guardian, February. 11, 2018.

- Taylor, Candacy (2020). Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America. Abrams Press. ISBN9781419738173.

External links [edit]

- Public domain digitized copies (1937–1963/64) of the Light-green Volume (via New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Inquiry in Black Culture)

- Introduction: "Navigating the 'Green Book'"

- Digitized 1941 edition of the Green Book in the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, with transcription

- Spring 1956 Dark-green Book, link to Google Maps display of over i,500 places listed, including a searchable index

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Negro_Motorist_Green_Book

0 Response to "Black Families in a Gas Station Jim Crow"

Post a Comment